WHO CONTROLS

WHAT YOU

PURCHASE?

By Anya Ibbitson, Isabella Karaiossifidi & Eva Kowalczyk

When purchasing anything, we all like to feel as though we are in control, and that the decision is our own. However, after a deep dive into some of the most popular brands, their advertisements and key features, it appears that this sense of control may be an illusion! We will explore the tactical use of enemy centric persuasion, nudging, anchoring and celebrity endorsement in marketing, on our behaviour.

ENEMY CENTRIC PERSUASION:

THE COLA WARS

The on-going battle between Coca-Cola and Pepsi for supremacy in the soft drink industry, dates back to the 1950s when Pepsi's corporate focus became "Beat Coke" (Yoffie, 2004). With such rigorous competition, both companies needed to get creative and think how they could persuade new customers to choose them, whilst keeping their existing ones happy and loyal. Through ads, experiments such as the renowned “Pepsi Challenge” and clever marketing, the two soda companies are constantly relying on psychological persuasion techniques that shape consumer perception and brand preference.

WINNING BY DEFINING A RIVAL

Pepsi’s “Tastes Better” campaign in Australia is an example of this rivalry. They used the “OK” part of “coke” to suggest that Pepsi Max would be a much more flavourful companion than Coke could ever be.“Why would you want something that tastes ‘OK’ when you could have Pepsi?” is essentially their message. The ad uses humour and competition to make the message more engaging and appeal to their consumers; people are more likely to share and remember a funny or clever ad, increasing brand recall and social engagement especially with younger crowds.

EMOTIONAL APPEAL

AND PERSONALISATION:

THE POWER OF CONNECTION

Consider Coca-Cola’s “Share a Coke” campaign.This approach created an emotional connection with consumers, encouraging them to find bottles with their own names or those of friends and family, finding purpose to choose Coke over Pepsi.

NUDGING

The art of nudging is exactly what it sounds like: encouraging a specific desired behaviour by imposing subtle environmental changes, rather than explicitly enforcing it. As humans, we are plagued by reactance and push back - basically, we don't like being told what to do (Brehm, 1966; Brehm & Brehm, 1981). Nudge marketing uses indirect prompts to influence customer behaviour and choice, giving the target the illusion of independent choice, and own decision making. It would be silly and a misconception to assume that we can avoid influencing others and their choices (Thaler & Sunstein, 2006), but who is controlling yours?

HERD MENTALITY NUDGE: FOLLOWING THE CROWD

A similar strategy is the use of reviews. Take Amazon, who display their reviews using stars that are easily visible next to the product. By making the customer aware of highly rated products, they are again nudging them in the direction of purchase. The MINDSPACE (messenger, incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect, commitment and ego) nudge framework (Dolan et al., 2012)’s ‘norms’ element underpins this idea of herd mentality nudging. If people have rated something highly you are more likely to buy it and comply with the ‘norm’, akin to how Netflix’s ‘Trending now’ or ‘Top 10’ convinces us to watch by evidencing their popularity.

CONTINUATION NUDGE:

FALLING VICTIM TO THE “FREE TRIAL”

We are all perhaps guilty of using all of the emails we can find to use as many free trials as possible, but how many of us have forgotten to end that free trial? Companies that require subscriptions such as Disney plus, often continue the subscription once the free trial has ended, unless the customer actively ends it.This relies on the ‘easy’ aspect of Halpern’s (2014) EAST (easy, attractive, social, timely) nudge framework. People are more likely to do something if it’s easy; when it becomes more difficult or time consuming, it becomes less attractive to them. Because of the extremely long and complicated process of going into your settings and pressing ‘unsubscribe’, we are often disinclined to do this. We are also quite talented at forgetting in these situations, and so, knowingly or unknowingly, we are nudged to continue the subscription.

INCENTIVES NUDGE: GIVE ME THE REWARDS

In the modern world where getting what you pay for simply isn’t enough, companies use reward schemes to nudge their consumers to their brand. Popular coffee shops such as Starbucks, Costa or Cafe Nero are generous enough to give you your 10th coffee free, and with a Tesco Clubcard your cheese goes from £5.40 to £4.25! These are often enough to incentivise us to shop with them.

Circling back to the MINDSPACE nudge framework (Dolan et al., 2012), these reward schemes rely on the ‘incentives’ aspect of the framework. The Tesco Clubcard is invaluable: it allows you to subsidise the prices of groceries, whilst also allowing you to collect points which you can spend on anything from more cheese to pairs of glasses. This multidimensional aspect of the Tesco reward scheme allows for incentives in all shapes and sizes, so much so that the absence of them may elicit a sense of loss aversion (Hodson, Kirilov & Vlaev, 2024). Essentially, we are persuaded more by the fear of missing out on these deals than the actual rewards themselves: either way, we are still persuaded by these incentives to shop at Tesco.

CELEBRITY ENDORSEMENT:

IS IT THE PERSON OR THE PRODUCT?

In summary, it’s both. Celebrities have a certain credibility about them for consumers, this kind of “if it’s good enough for Taylor Swift - it’s good enough for me!” mentality. Having a public figure as the face of your product increases brand awareness, enhances brand recall, and drives sales. Elberse & Verleun (2012) found that when sports celebrities endorsed products, companies saw an average 20% sales increase. According to Fang & Jiang (2015), this works through heuristic persuasion - where consumers rely on emotional connections rather than logic. People trust recommendations from those they admire, and celebrities often possess a potent mix of attractiveness, credibility, and emotional appeal, making their endorsements highly persuasive.

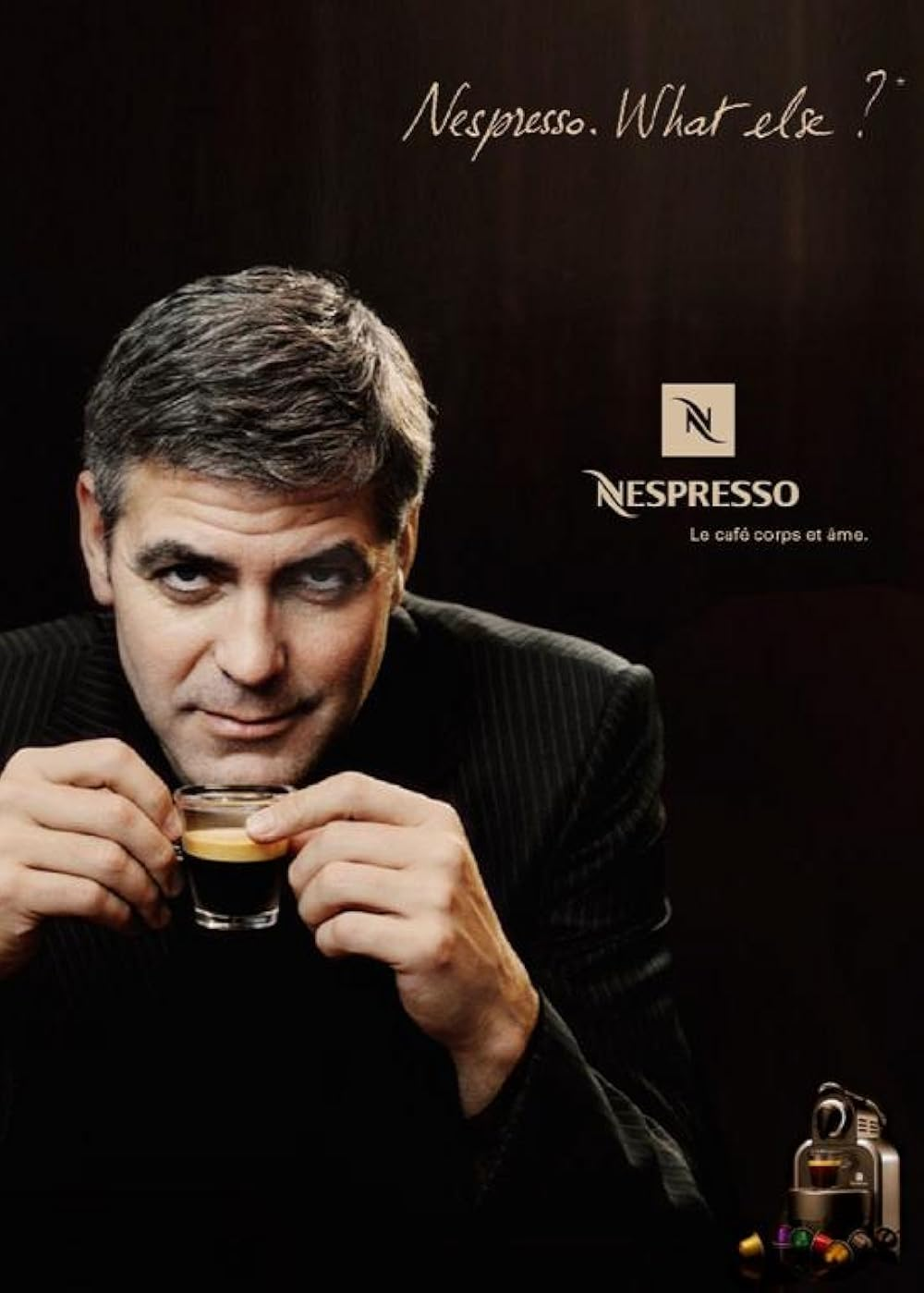

Can you drink your Nespresso coffee without picturing George Clooney? What about when you order from Just Eat does Katy Perry play in your head? Had you even heard of Just Eat before her catchy jingle came out? A well-matched celebrity can positively influence brand perception, leading to higher consumer engagement and sales (Moraes et al., 2019). It’s not just about any celebrity it's about it being the right one, who fits the brand and consumers can envision using the product (Liang et al., 2022). This is what makes it all that more convincing.

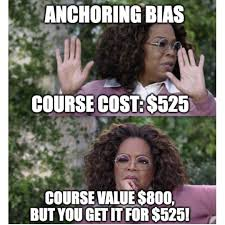

The anchoring effect massively biases consumers towards the initial information that they receive (Furnham & Boo, 2011), such that their decision will be influenced in some way by or frequently align with it (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). From a marketing standpoint however, perhaps this initial fixation can have multiple advantageous outcomes.

PRICING AND VALUE

In this situation there are two types of customer. Consumer one may be encouraged to purchase a subscription due to the initial display of a high priced option, which then makes subsequent lower priced subscriptions more appealing (Tanford, Choi & Joe, 2019). Alternatively, consumer two may be anchored by their initial exposure to an appealing subscription with all benefits, view subsequent options as less beneficial and of worse value than the initial one, therefore being persuaded by the initial offer.

Consider the case of Apple. You need to buy a new phone, and you’re harassed by the $1199 IPhone 16 Pro Max. Initially you may be taken aback by the massive number in front of you; however, anything you now view (even the $799 standard IPhone 16) appears much more affordable!

LIMIT ANCHOR: THE ILLUSION OF HIGH DEMAND

Customers are not only anchored by price, they could be influenced by sales for example (Dellarocas, 2003). Relying on this aspect of marketing, in a stroke of marketing genius, KFC Australia have reconstructed the potato into a must-have item. By branding their fries as “a deal so good you can only buy 4” (Blaess, 2022) they create a sense of artificial high demand.

SO,

WHO CONTROLS

WHAT YOU

PURCHASE?

Ultimately, while we tend to think we have complete freedom when it comes to our purchasing decisions, brands thrive because they are clever, using psychological techniques to subtly guide us toward specific choices. By deploying enemy-centric persuasion, nudging us through subtle environmental cues, anchoring our perceptions of value, and using the persuasive power of celebrity endorsements, companies successfully influence our buying behaviour. Such tactics used by companies tap into our emotions and social instincts, often without us even realising it.

However, being aware of these strategies can restore some of our control. Recognising when we are being nudged or anchored allows us to pause, reconsider, and possibly make decisions that are truly ours. Rather than rejecting these influences outright, awareness helps us to become more mindful consumers, consciously deciding how much we let marketing tactics shape our decisions.

Next time you grab a Pepsi, binge-watch the top Netflix show, or upgrade to the latest iPhone, stop and consider, whose choice was this, really?

REFERENCES

Blaess, N. (2022). How Ogilvy used psychology to increase sales of KFC French fries by 56%. Retrieved from https://www.nineblaess.de/blog/how-ogilvy-used-psychology-to-increase-sales-of-kfc-french-fries-by-56/

Brehm, J. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. APA PsycNet. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1967-08061-000

Brehm, S. S., & Brehm, J. W. (2013). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. Academic Press.

Dellarocas, C. (2003). The digitization of word of mouth: Promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms. Management Science, 49(10), 1407–1424. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.49.10.1407.17308

Dolan, P., Hallsworth, M., Halpern, D., King, D., Metcalfe, R., & Vlaev, I. (2012). Influencing behaviour: The MINDSPACE way. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(1), 264–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.10.009

Fang, L., & Jiang, Y. (2015). Persuasiveness of celebrity-endorsed advertising and a new model for celebrity endorser selection. Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 5(8), 153–173.

Furnham, A., & Boo, H. C. (2011). A literature review of the anchoring effect. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2010.10.008

Hodson, N., Kirilov, G., & Vlaev, I. (2024). The MINDSPACE expanded framework (MINDSPACE X): Behavioral insights to improve adherence to psychiatric medications. Current Opinion in Psychology, 101973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2024.101973

Kameda, T., & Hastie, R. (2015). Herd Behaviour. Emerging trends in the social and behavioural sciences: An interdisciplinary, searchable, and linkable resource, 1-14.

Moraes, M., Gountas, J., Gountas, S., & Sharma, P. (2019). Celebrity influences on consumer decision making: new insights and research directions. Journal of Marketing Management, 35(13-14), 1159–1192. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257x.2019.1632373

Liang, S.-Z., Hsu, M.-H., & Chou, T.-H. (2022). Effects of Celebrity–Product/Consumer Congruence on Consumer Confidence, Desire, and Motivation in Purchase Intention. Sustainability, 14(14), 8786. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148786

Service, O., Hallsworth, M., Halpern, D., Algate, F., Gallagher, R., Nguyen, S., Ruda, S., Sanders, M., Pelenur, M., Gyani, A., Harper, H., & Kirkman, E. (2014). EAST: Four simple ways to apply behavioural insights. Retrieved from https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/BIT-Publication-EAST_FA_WEB.pdf

Tanford, S., Choi, C., & Joe, S. J. (2019). The influence of pricing strategies on willingness to pay for accommodations: Anchoring, framing, and metric compatibility. Journal of Travel Research, 58(6), 932–944. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518793037

Thaler, R., & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. APA PsycNet. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-03730-000

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Yoffie, D. B. (2002). Cola wars continue: Coke and Pepsi in the twenty-first century. Harvard Business School. Retrieved from https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=28760

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.