The problem:

Stress is a common part of university life. Abouserie (1994) found that high stress levels within 675 second year undergraduate students was linked to examinations and locus of control, with students who believed they were in control of lives being significantly less stressed. Consequently, high stress levels often results in poor mental health; mental health among university students is becoming a growing concern (Eisenberg, Gollust, Golberstein, & Hefner, 2010). In a 2005 national survey of undergraduate students, 10% of students reported “seriously considering attempting suicide” (American College Health Association, 2006) and this percentage is consistently on the rise. However, according to Neely and colleagues (2009) self-compassion and availability of support significantly improves well-being within college students and may act as a buffer against stress and poor mental health. Responding to this research, we endeavoured to improve the well-being of students at the University of Warwick by encouraging students to be kind to others.

Upon researching, we came across the organisation ‘Random Acts of Kindness’, so we decided to reach out to them to ask about their motivations and for some tips to inspire us with our kindness project.

This made us think about whether kindness is well-practiced amongst the University population, so we asked 20 students at the University of Warwick whether they thought they could be kinder to others or whether others could be kinder to them. We found that 90% of students admitted they do not practice kindness enough and that others could be kinder to them, which motivated us to create this project.

Our intervention:

Our intervention involved attempting to increase kindness through small daily challenges, specifically targeted at university students. Research has found that counting the number of acts of kindness towards others in one week, hence being aware of your kind behaviour towards others, increases happiness and gratefulness in students (Otake, Shimai, Tanaka-Matsumi, Otsui & Fredrickson, 2006). One study assigned participants to either perform kind acts, new/novel acts or no acts for 10 days and found that life satisfaction ratings increased for those who performed kind or novel acts, and participants in these groups also rated significantly higher life satisfaction than the control group (Buchanan & Bardi, 2010). This literature supports our intervention, providing evidence that happiness can be increased through small acts of kindness, and recognition of these acts.

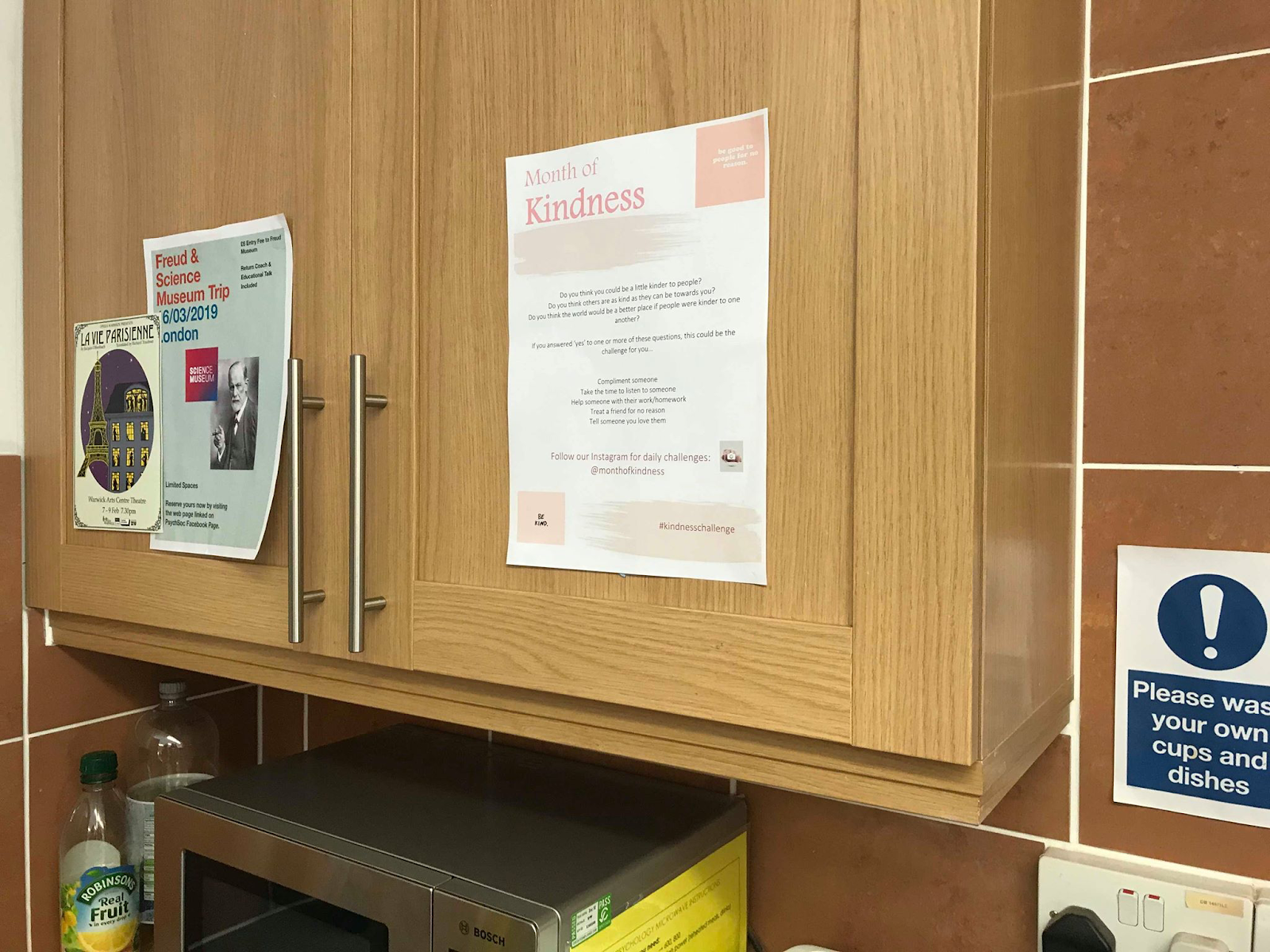

In order to reach the target audience, we decided to set up an Instagram page called ‘MonthofKindness’ where we posted daily kindness challenges for 30 days, as Instagram is a commonly used app for the University population. We also posted Instagram stories throughout the day to encourage and inspire our followers, and used the hashtag ‘#kindnesschallenge’ to encourage anyone else looking for kindness inspiration to take part.

Alongside this, we took part in a discussion on University of Warwick radio programme (RAW) about why kindness is important, addressing reasons why we started the project, suggesting some kindness challenges and advertising the Instagram page. For those who do not use Instagram or listen to RAW, we put up posters around the university campus in popular places. By targeting a range of platforms (e.g. radio and social media) and spreading posters around the university and off campus accommodation, we increased the availability of the project to others.

According to the Availability Heuristic theory (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973), if something is easily accessible, it comes to mind easily and is seen as important.

According to the Availability Heuristic theory (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973), if something is easily accessible, it comes to mind easily and is seen as important.

The Instagram page (https://www.instagram.com/monthofkindness/) was set up with a post every day showing different challenges, a caption explaining each of the challenges featuring the hashtag #kindnesschallenge, and Instagram Stories every day to offer further inspiration and examples for the challenges, polls, and kindness quotes.

Psychological and persuasion techniques used:

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991), suggests that attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control all feed into a person’s intention, which leads to behaviour.

We aimed to appeal to the first three components of the theory with our audience to increase their intention to be kinder.

- Attitude: Does our audience care about this topic? Why should they care about this topic? Kindness is an attribute commonly spoken about in religions, in schools, and as a Golden Rule. It is something that most people would be proud to admit they possess, therefore it is personally significant. To help maintain a positive attitude of kindness, we emphasised that it doesn’t cost much to be kind and so included challenges that did not cost the audience anything e.g. smiling at strangers. We also emphasised that change can be created by everyone, that change starts with you. Additionally, through captions and Instagram stories we spoke about the benefits about being kind, both for the giver and the receiver to reinforce a positive attitude.

Subjective Norms: Are other people doing the same? According to Ajzen (1991), knowing that other people are also participating in the behaviour and that it is acceptable to do so, increases the chances that the behaviour will occur. We implemented this by asking people to respond to the challenges, letting us and others know when they have completed the challenge successfully through polls. When other people liked the posts this also suggested that they had participated in the challenges and are implementing the behaviour in their lives. Consequently, these responses influences others to change their behaviour and be kind to others.

Perceived behavioural control: This is the belief that you are capable of the behaviour. To help our audience feel they could achieve the challenges set to them, we repeated daily to our audience that everyone is capable of being kind. The Instagram stories included images with captions saying ‘you can’ and ‘everyone has the ability to be kind’. We made each challenge clear and easy to follow, making it easy for the audience to complete the task. This increased their self-efficacy and the likelihood their attitude is changed and the behaviour occurs.

We attempted to use implementation intentions through Instagram stories, such as this one - outlining the who, what, when, why and how to try to encourage people to implement kind behaviour today. Additionally, as each task was posted daily, it allowed people to focus on one act of kindness that they could do today.

The foot-in-the-door technique uses previous commitment and consistency to increase the chances that a behaviour will occur (Freedman & Fraser, 1966). Our project used this method to help engage people to complete all challenges. After having completed the first few small challenges, people have committed to being kinder, and will therefore are more likely to be consistent and perform later challenges. We also tried to increase the level of kindness to slightly bigger acts as the days went on. For example, on day 5 the challenge was to smile at 5 strangers, then later on day 16 the challenge was to pay for the drinks on the table next to them in a café. There is a considerable jump here, but research suggests that when people have committed to small acts, they are more likely to engage in bigger acts later, e.g. people asked to wear a pin advertising American cancer society were 2X as likely to give a donation the next day than those not wearing a pin (Pilner, 1974).

The future

In terms of our success, we gained 986 impressions on our Instagram account, which refers to the total amount of times our posts have been seen, and we received praise messages from other kindness accounts and students who were inspired by the project. In the future, we will use the account to post further quotes about kindness and potentially more monthly challenges to spread kindness further. This is a relatively small scale project, but as the ‘Random Acts of Kindness’ group said, even the smallest acts can change someone’s life.

References

Abouserie, R. (1994). Sources and levels of stress in relation to locus of control and self esteem in University students. Educational Psychology, 323-330.

American College Health Association. (2006). American college health association national college health assessment. Journal of American College Health, 55, 5-16.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

Buchanan, K. E., & Bardi, A. (2010). Acts of kindness and acts of novelty affect life satisfaction. The Journal of Social Psychology, 150, 235-237.

Eisenberg, D., Gollust, S. E., Golberstein, E., & Hefner, J. L. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 534-542.

Freedman, J. L., & Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 195-202.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69-119.

Neely, M. E., Schallert, D. L., Mohammed, S. S., Roberts, R. M., & Chen, Y.-J. (2009). Self-kindness when facing stress: The role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students' well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 88-97.

Otake, K., Shimai, S., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., Otsui, K., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindness intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 361-375.

Pliner, P., Hart, H., Kohl, J., & Saari, D. (1974). Compliance without pressure: Some further data on the foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 17-22.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5, 207-232.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.