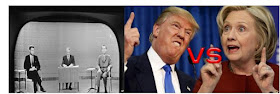

“That

night, image replaced the printed word as the natural language of politics.” (Baker, 1992)

Kennedy vs Nixon

US politics is particularly prominent at the moment and

going a full day where it isn’t highlighted in the media is unlikely. The

debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have specifically attracted a

lot of attention from the public, with the first debate breaking records with

an audience of 84 million viewers and the subsequent two averaging at around 70

million viewers.

But where did it all begin? On the 26th of

November 1960, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon competed in the first

televised debate. This particular debate has now become famous for highlighting

the role television plays in politics. Mainly because many accounts of the

debate have suggested a viewer – listener disagreement, where those who watched

the debate on TV thought Kennedy had won but those that listened to the debate

on radio thought Nixon to be the victor. Although now it has been classed as a

myth with little evidential support (Vancil & Pendell, 1987), it sparked

interest in how the personal image of candidates on TV can influence voters

overall evaluations.

Druckman (2003) revisited this notion that individuals will

have different evaluations of the debate and the candidates (Kennedy vs Nixon)

depending on the medium the debate is portrayed on. The findings were

consistent with accounts of the debate, that TV image does matter and could have

played an important role in the first Kennedy – Nixon debate. TV viewers were

significantly more likely to think Kennedy won the debate than audio (radio)

listeners and viewed Kennedy as having significantly more integrity than Nixon.

Interestingly, it was found that watching the debate on TV primed participants

to rely more on image (i.e integrity) and this played a significantly more

important role for viewers than for listeners. Listeners relied only on their

perceptions of leadership effectiveness compared to TV viewers who relied on

both leadership effectiveness and image in evaluating the candidates. Moreover,

the influence of perceptions of image for TV viewers lead to a decreased

influence of whether the candidates and respondents agreed with the same issues

but this remained a significant factor for listeners.

What is it about image that persuades people to think

candidates would be better presidents?

Todorov and colleagues (2005) found that

inferences of competence from facial features with exposures of just 1 second

could correctly predict voting behaviour of US election outcomes. Those that

were perceived to be more competent from their facial features were more likely

to have won their elections. Mattes and colleagues (2010) found results

consistent with this but with other positive and negative traits as well. In

their study images of the two candidates in the race were shown together for

both 33 ms and one second and participants quick judgements correlated with

which candidates won the elections. As you can see from the table below those

perceived to have more of the positive traits were more likely to have been

chosen by the participants and actually have won their elections. Those with

negative traits were less likely to be chosen by participants and less likely

to have won their elections. Both Todorov et al (2005) and Mattes et al (2010) saw this as support that the evaluations of candidates individuals make are quick and effortless processes.

So how does this research relate to the Kennedy – Nixon

debate?

What was it about Nixon that lead to him being perceived so

poorly on TV compared to radio? According to Hughes (1995), Nixon was still

recovering from a knee surgery which he had spent time in hospital for which

added to his already pale complexion and lead him to shift his weight a lot

during the debate making him look uncomfortable. Moreover, in the black and

white TV his dark beard made him look unshaven which his team attempted to

cover up with ‘lazy shave cream’ but only added to his disastrous image making

him sweat more under the extra lights requested by his team. All of this lead

to Nixon being perceived as sickly and uncomfortable and thus possibly less

competent. In contrast, Kennedy had spent time touring California and was subsequently

tanned making him look healthy and well rested. Additionally, Kennedy wore a

dark suit, making him stand out against the light background, compared to

Nixon’s light grey suit which meant he blended into the background. Also during

the debate, Kennedy directed his focus towards the camera and was seen making

notes in reaction shots which made him appear self-confident. Whereas, Nixon

often directed his focus towards Kennedy and was caught checking the time

during reaction shots which lead him to being perceived as ’shifty eyed’ and

thus less trust worthy. The comparison between the candidates of these

non-verbal cues (only seen by those who watched the debate on TV) was the most

likely reason that Nixon was reported to have lost the debate on TV compared to

those that just listened to what he said on radio.

How can Theories of Persuasion explain this?

Petty and Cacioppo (1986) have proposed a dual

process model called the Elaboration Likelihood Model which illustrates how

individuals process information when they are persuaded (or not). Persuasion

can take place via two routes Central or Peripheral. The central route refers

to higher cognition or processing of information (arguments) and this route is

taken when there is desire for beneficial outcomes, motivation to know and

control and often when the individual cares about the topic. The peripheral

route refers to lower cognition or processing most likely due to limited

cognitive resources or capacity to process and often not a strong argument is needed

as other peripheral cues or heuristics are used to make a decision. From what

has been described above (how individuals

can be influenced by appearance of candidates) it appears that often people may

rely on heuristics (cognitive short-cuts) to make judgements about candidates.

This seems counter-intuitive, especially when thinking about candidate

elections for presidency, you would think individuals would use the central

route as elections of this nature would be important to them and there would be

a desire for beneficial outcomes. However, a paper by Lau and Redlawsk (2001)

suggests otherwise: stating that the ‘average’ individual tends to be less

motivated when making political decisions and uses the peripheral route. Lau

and Redlawsk (2001) identified 5 types of politic heuristics and found that

these were employed the majority of the time by participants (see table below). One of which is

specifically relevant, ‘candidate appearance heuristic’. This heuristic refers

to when individuals makes judgements based on specific cues about the physical

appearance of a candidate (Reilly). This is particularly worrying as findings

from Lenz and Lawson

(2011) suggests that there is a greater reliance of this heuristic in those

with less political knowledge and that ‘appealing-looking’ politicians will

benefit more from increased television exposure.

So

it appears that a candidate’s TV image is important as people tend rely on

inferences made about appearance when making voting decisions. If you want to

run for the US presidency do not make the same mistakes as Nixon. But then

again, America voted in Donald Trump so it can not be the only factor given the

things we see on TV about him.

(see

part 2 for some of the different persuasive techniques Trump employs in his

debates with Hillary Clinton).

References:

Baker, R. (1992, November 1st). The 1992 Follies. The New York Times.

Druckman,

J. N. (2003). The Power of television images: The first Kennedy‐Nixon debate revisited. Journal

of Politics, 65(2), 559-571.

Hughes,

S. R. (1995). The effects of nonverbal behavior in the 1992 televised

presidential debates (Doctoral

dissertation, Texas Tech University).

Lau,

R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive

heuristics in political decision making. American

Journal of Political Science, 951-971.

Lenz,

G. S., & Lawson, C. (2011). Looking the part: Television leads less

informed citizens to vote based on candidates’

appearance. American Journal of Political Science, 55(3),

574-589.

Mattes, K., Spezio, M., Kim, H., Todorov, A., Adolphs, R.,

& Alvarez, R. M. (2010). Predicting election outcomes from positive

and negative trait assessments of candidate images. Political Psychology, 31(1),

41-58.

Reilly, B. D. The Ties That Bind: Candidate Appearance and

Party Heuristics.

Todorov,

A., Mandisodza, A. N., Goren, A., & Hall, C. C. (2005). Inferences of

competence from faces predict election

outcomes. Science, 308(5728), 1623-1626.

Vancil, D. L., & Pendell, S. D. (1987). The myth of

viewer‐listener disagreement in the first Kennedy‐Nixon debate. Central

States Speech Journal, 38(1), 16-27.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.